While the history of sports journalism only spans a couple of centuries, that time has seen many debates over media members’ fandom.

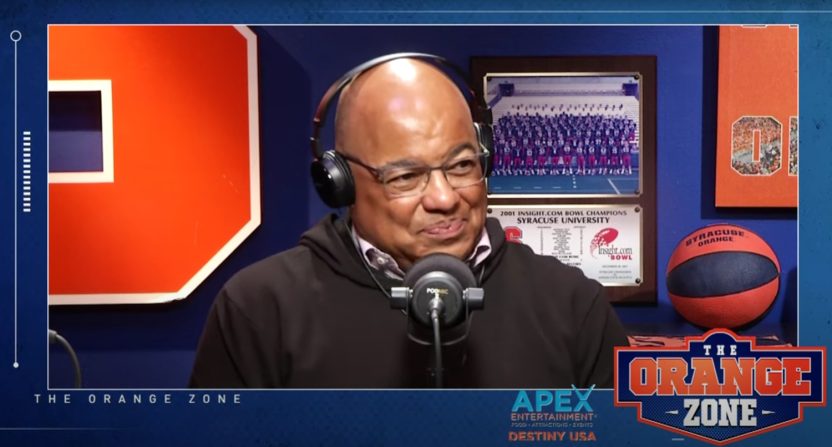

Those debates have produced dramatically different answers over time, from clearly declared biases in early coverage to a strong focus on neutrality for much of the late 20th and early 21st centuries to the last decades’ pushes for media members to reveal and incorporate personal fandom of teams. Amidst that, comments from NBC’s Mike Tirico on the Syracuse-focused The Orange Zone podcast last week stood out.

On that podcast with Samatha Croston and Rachel Culver, Tirico discussed his lack of general lack of fandoms (except for Syracuse college sports, which he doesn’t tend to cover) right off the start.

He said, “I’m not a fan, because you know part of your job is that ‘I cannot be a fan of the Lions, or the Vikings, or the Packers, because you’re the home-team announcer for both teams when you do Sunday Night Football, so over time, you just get neutered to those emotions.”

Yes, it’s ironic he did this on a podcast with a backdrop filled with Syracuse logos, but he does spell out why he thinks that’s an exception, with him not covering their sports. He went on to cite his distaste for the recent trend of national figures explicitly working fandom into their coverage:

“You start covering it nationally, and realize you can’t have fandom seep in,” Tirico said. “Now, people do now, and it bothers me. I don’t like watching SportsCenter or other shows on ESPN where the anchors are talking about who they’re fans of. Like, who cares? I don’t care. I would much rather know the 20 seconds about something related to that team that I don’t know, as opposed to your fandom.

“Now, generationally, people kind of like it because they can relate to the anchors a bit more, so I get it. I’m just saying my personal choice is — that’s the way I was brought up as a journalist. I don’t care if you’re a Republican or a Democrat. I don’t care if you’re a Phillies fan or a 49ers fan. Your job is to tell me the news. And in sports talk, that’s a different world. But when you’re doing the facts, and you’re in the middle of a game, I don’t want to hear.”

“Stephen A. Smith is great, and he’s a friend, and he’s done a wonderful job,” Tirico adds. “I don’t want time wasted during the NBA halftime [show] telling me your feelings as a Knicks fan. I want to hear about the game, and what I missed, and what I need to look forward to. But, again, that’s just a personal way of consuming sports, and I’m a little bit old school when it comes to that. I’m old, so I’m glad to be old school.”

Not everyone subscribes to Tirico’s logic here, and that’s not really even his point. He recognizes that he’s in the minority now and says this is “just a personal way of consuming sports.” But Tirico’s comments tie into a long tradition of back-and-forth swings in the discussion of sports media fandom, with the avowed fandom side riding particularly high. They provide a rare case where those of us from the Neutral Planet who root for the story can see ourselves represented in current sports media.

“Rooting for the story” itself needs some discussion. It’s been a widely-cited line by sports journalists over the years, especially in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, in response to suggestions of bias. It implies hoping for the outcome that makes for the best story rather than one benefiting a specific team or athlete, and it ties into overall media (and newspapers especially), shifting news coverage away from highly partisan origins to a more neutral (at least in theory) approach. And that shift also happened in sports, with a lot of early coverage being quite partisan towards the local team, but with that shifting over time.

Current St. Bonaventure associate professor Brian Moritz of Sports Media Guy fame has a detailed discussion of this concept in his 2014 Ph.D in Mass Communication dissertation from Syracuse (available to read for free here). Moritz, a long-time newspaper journalist before entering academia, based that dissertation on his interviews with newspaper journalists across the U.S. on norms, routines, practices, and changes to their jobs. It’s appropriately titled “Rooting for the story: Institutional sports journalism in the digital age.” Here’s one key section:

Sports journalists have a saying they often refer to when discussing their jobs: Rooting for the story. The phrase came up several times over the course of the interviews conducted for this research. It’s used as a central description of the job and also often as a defense when readers accuse reporters of rooting for — or more frequently against — a given team. In many ways, it’s a central, normative belief that encapsulates the sports journalists’ job. It distinguishes journalists as a professional field from sports fans. Fans live and die with their teams’ successes and failures, their wins and losses. Sports journalists don’t care who wins and loses. They have a job to do either way. They root for the best story — the most interesting, compelling account to them and to their readers.

That research and its results would look quite different if conducted in 2025. There would likely be interviewees from TV, radio, and/or digital publications in addition to newspapers, and there would probably be many more journalists openly admitting fandoms and placing less emphasis on the “rooting for the story” concept. (Indeed, Moritz is very open about his own fandoms; he had a significant discussion of his Bills’ fandom, and fandom in general, around Damar Hamlin’s 2023 injury.) But how did we get to that point?

Two of the most notable figures in this shift are Bill Simmons and Will Leitch, and is that ever a pairing. The Sports Guy and the Deadspin founder have had plenty of disagreements over the years. But both of them were early, passionate, and prominent advocates for displaying fandom in sports coverage, with that illustrated not just in digital writing and podcasting but even in books such as Simmons’ Now I Can Die In Peace on the Red Sox’s 2004 title and Leitch’s 2008 God Save The Fan manifesto. The Amazon description of that latter one (full title: God Save the Fan: How Steroid Hypocrites, Soul-Sucking Suits, and a Worldwide Leader Not Named Bush Have Taken the Fun Out of Sports) really makes it clear where Leitch is coming from, with “Always a fan first and a sportswriter second.”

Leitch, Simmons, and their numerous contemporaries played huge roles in the sports blog era. A large part of that era for many was embracing their fandom while still providing coverage, producing a lot of excellent work that previously would not have been published. That’s led to shifts where many professional sportswriters openly admit to particular fandoms, including my fantastic colleagues at this site. It also led to some of the shifts Tirico is referencing today, even in other mediums such as TV, where ESPN personalities such as Scott Van Pelt and Stephen A. Smith openly discuss events through the prism of their fandoms.

None of that is inherently bad. We’re not here to repeat past get-off-my-lawn screeds about “these fans these days,” such as Kevin-Paul Dupont’s infamous 2012 rant about “replacement journalist” bloggers, or to say anchors can’t show fandom on TV. But it’s worth looking in more detail at some of what was explicitly said in that early era, and what it’s led to. A 2009 Deadspin column from Leitch (at a point where he’d turned site control over to A.J. Daulerio but was still contributing) stands out there:

One of the most nonsensical constructs of sports journalism is the notion that your reporter is supposed to be “impartial.” I think this is some sort of misguided offshoot of political journalism. There, if you are “biased” against a candidate or party, at least theoretically, you could somehow skew coverage and public perception to fit your own agenda. I don’t think this happens, but I suppose it’s possible.

In sports, we have actual winners and losers, real, live, official contests that help us decide who is successful and who is not. If I were covering the Chicago Cubs, I could write whatever I wanted to about them, and it would not change the results of their games. (Unless I screamed my stories in their ear when they were trying to hit or something, though I have a feeling someone would eventually stop me from doing that.) Yet we go on, pretending that our reporters have no personalities of their own, that they are mere robots here, that they weren’t once kids with their own rooting interests, their own posters on their bedroom walls. Hey, everyone: Peter King grew up cheering for the Giants. How can we ever trust him again?

I think this is shifting, though, and I think it’s a good thing.

As discussed above, that’s shifted incredibly, perhaps even to a degree Leitch didn’t envision. One point of Leitch’s in that column is well-taken indeed; disclosed bias is much better than hidden bias. But the specific point Leitch made, “pretending that our reporters have no personalities of their own,” has been grating at me for decades. Who’s to decide that rooting for the story isn’t a valid personality or a valid rooting interest?

The specific fandom lines in sports media are still being debated. Some still find it inappropriate for writers to pose with trophies or celebrate a win, others don’t, or think it varies depending on circumstance. Some want their SportsCenter to focus on Scott Van Pelt’s perspective on Maryland basketball or their NBA halftime show to emphasize Stephen A. Smith’s perspective on the Knicks, others don’t. And this certainly isn’t a call that everyone should abandon stated fandoms or that admitted fans shouldn’t work in sports media. The last couple of decades’ changes there have led to a lot of positive coverage developments and have appealed to a lot of fans.

But what is clear is that the landscape has dramatically shifted over the last decades to journalists’ fandom being almost assumed. Indeed, we’re at a point where even revealing that you work in sports media often leads to the next question: “Who do you root for?” For some of us, that actually is journalism (not the horse), or more specifically, the best story. And Tirico’s public representation of that currently seldom-seen point of view is appreciated.