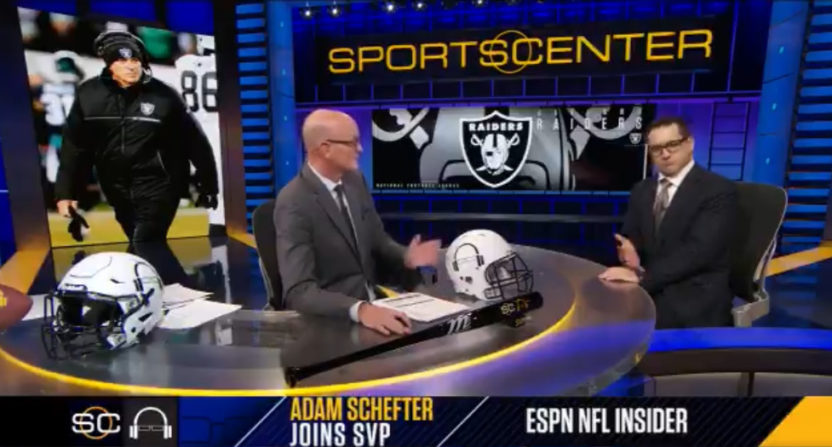

The NFL is a league where transactional (coaching moves, trades, player signings and cuts, and so on) news has a lot of value, which has led to the prominence of national reporters like ESPN’s Adam Schefter (seen above on SportsCenter with Scott Van Pelt) and NFL Network’s Ian Rapoport, thanks to their ability to regularly break news across the league. But some reports wind up being completely wrong, and others wind up being correct at the time but then looking bad when the situation changes.

Paul Kuharsky, the former Tennessee Titans reporter for The Tennessean and ESPN who started his own subscription site covering the Titans last fall, has an interesting post up titled “Why NFL reporters seem so reluctant to admit when they are wrong.” That post contains both his own thoughts and comments from national figures like Schefter, Rapoport and Pro Football Talk’s Mike Florio.

The post is paywalled (subscriptions to Kuharsky’s site are $5.99/month or $65.89 for a year), but he provided Awful Announcing permission to quote part of it. Here are some of the comments from Rapoport and Florio:

“I think Twitter keeps everyone humble and accountable because you know when you report something and then either you were wrong or the situation did literally change, then someone will send your original tweet back to you,” said Ian Rapoport of NFL Network. “And to me, that keeps us all accountable. …Rarely do one of us come out and say I was wrong, but everyone knows what we reported and it’s all out there and very public. And everything I report I know that I am now reporting this very, very publicly.”

…”When I’m wrong I always admit it; that’s probably one of the benefits of owning the platform,” [Florio] said, though he couldn’t point to an example. “The bigger challenge is trusting the right people when aggregating, because their mistake (e.g., the Shreveport TV station that turned “someone died on the Terry Bradshaw passway” into “Terry Bradshaw passed away”) becomes the aggregator’s mistake.”

And Schefter had some interesting thoughts on his story about Marvin Lewis planning to leave the Bengals, which didn’t come to pass:

“The plan was for (Lewis) to leave, with a small chance (to stay). Like you say, ‘you’re wrong.’ That’s right. I mean in the end your story was wrong.”

“But was it wrong? I didn’t say he was leaving, I said he was planning to leave. That was the wording I used. If I plan to go to dinner and we don’t go to dinner, things happen. Life happens. That’s the hard part of these jobs.”

There are plenty of further notable thoughts from those reporters and from Kuharsky himself in there, and he argues that there should perhaps be more transparency and more reporters admitting when they were wrong. He talks about the mistakes he’s made himself over the years and how he’s corrected them, and cites his former editor at the New York Times, Cory Dean, as saying “When you’re wrong, get right as fast as you can.” And that’s probably good advice for journalists in general, and it could probably be used by some NFL reporters a bit more.

The latest

- AA Podcast: Chris Fallica on Lee Corso, ‘College GameDay,’ ‘Big Noon Kickoff,’ and more

- Scott Hanson says ‘the process is ongoing’ on ‘RedZone’ extension, talks NFL Draft

- Bleacher Report’s Tyler Price on NFL Draft show, new league partnership: ‘This is our Super Bowl’

- ‘Celtics City’ director on working with Bill Simmons, Connor Schell: ‘We were surrounded by some of the most incredible minds’

The peril comes if the couching becomes too widespread, though, and Kuharsky rightly notes that it can be an even bigger issue for others, when “less prevalent and less plugged in reporters use “expected to” or “could” as a crutch that simply buys them leeway to be wrong.” Anything “could” happen, so the burden for NFL reporters should be only using that kind of language when there’s actually a good chance of the thing in question happening.

Overall, Kuharsky makes good points about the importance of accountability as well as accuracy, and he makes a good argument that national reporters should perhaps openly correct themselves more and admit their errors. But it’s also interesting to hear the thoughts of Rapoport, Florio and Schefter on this, and to hear how they do keep accuracy in mind and how they handle reporting changing stories.

It’s good to see this topic being discussed; it’s something reporters should keep in mind, and something fans should keep in mind. The reporters who both regularly get it right and admit their mistakes publicly on the occasions when they don’t seem like better sources to trust than the ones who don’t do either.